sundar-pichai.md 13 KB

+++ title= "Google boss Sundar Pichai warns of threats to internet freedom" date= 2021-07-22T00:50:34+08:00 tags = ["video-marketing", "text to video"] type = "blog" categories = ["marketing"] banner = "https://i.imgur.com/jdQb3ZH.jpg" +++

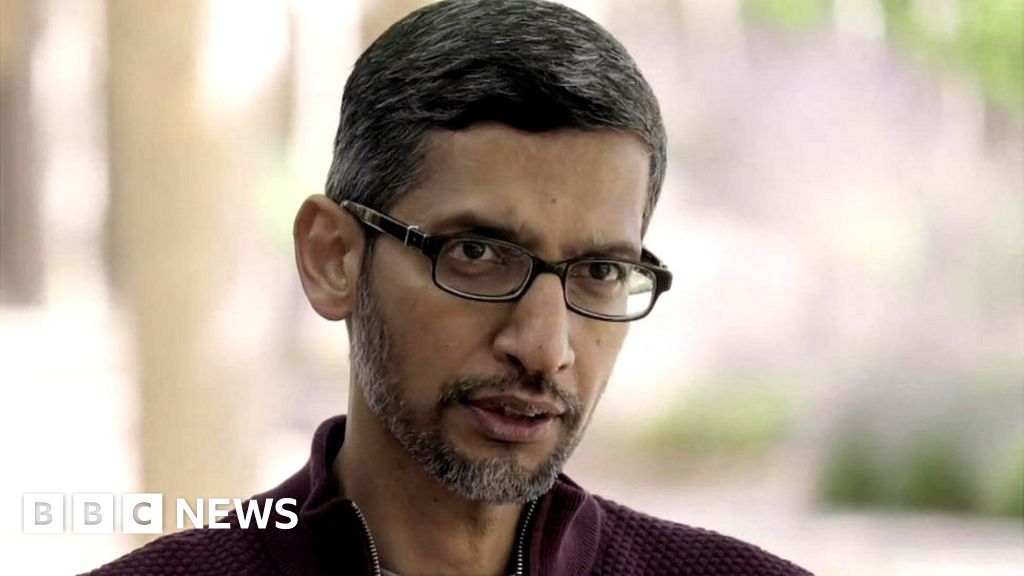

Google boss Sundar Pichai warns of threats to internet freedom

The free and open internetis under attack in countries around the world, Google boss Sundar Pichai has warned.

He says many countries are restricting the flow of information, and the model is often taken for granted.

In an in-depth interview with the BBC, Pichai also addresses controversies around tax, privacy and data.

And he argues artificial intelligence is more profound than fire, electricity or the internet.

Pichai is chief executive of one of the most complex, consequential and rich institutions in history.

The next revolutions

I spoke to him at Google's HQ in Silicon Valley, for the first of a series of interviews I am doing for the BBC with global figures.

As boss of both Google and its parent company Alphabet, he is the ultimate leader of companies or products as varied as Waze, FitBit and DeepMind, the artificial intelligence pioneers. At Google alone he oversees Gmail, Google Chrome, Google Maps, Google Earth, Google Docs, Google Photos, the Android operating system and many other products.

But by far the most familiar is Google Search. It's even become its own verb: to Google.

Over the past 23 years, Google has probably shaped the mostly free and open internet we have today more than any other company.

According to Pichai, over the next quarter of a century, two other developments will further revolutionise our world: artificial intelligence and quantum computing. Amid the rustling leaves and sunshine of the vast, empty campus that is Google's HQ in Silicon Valley, Pichai stressed how consequential AI was going to be.

"I view it as the most profound technology that humanity will ever develop and work on," he said. "You know, if you think about fire or electricity or the internet, it's like that. But I think even more profound."

Artificial intelligence is, at base, the attempt to replicate human intelligence in machines. Various AI systems are already better at solving particular kinds of problems than humans. For an eloquent exposition of the potential harms from AI, try this essay by Henry Kissinger.

Quantum Computing is a totally different phenomenon. Ordinary computing is based on states of matter that are binary: 0 or 1. Nothing in-between. These positions are called bits.

But at the quantum, or sub-atomic level, matter behaves differently: it can be 0 or 1 at the same time - or on a spectrum between the two. Quantum computers are built on qubits, which factor in the probability of matter being in one of various different states. This is mind-boggling stuff, but it could change the world. Wired has an excellent explainer.

Pichai and other leading technologists find the possibilities here exhilarating. "[Quantum] is not going to work for everything. There are things for which the way we do computing today would always be better. But there are some things for which quantum computing will open up an entire new range of solutions."

Pichai rose through the ranks of Google by being the most effective, popular and respected product manager in the company's history.

Neither Chrome, the browser, nor Android, the mobile operating system, were his idea (Android was for a while led by Andy Rubin). But Pichai was the product manager who led them, under the watchful eyes of Google's founders, to global domination.

In a sense, Pichai is now product managing the infinitely greater challenges of AI and quantum computing. He is doing so as Google faces a daily barrage of scrutiny and criticism on several fronts - to name but three: tax, privacy, and alleged monopoly status.

Taxing tech

Google gets defensive on matters relating to tax.

For several years, the company has paid huge sums to accountants and lawyers in order to legally reduce their tax obligations.

For instance, in 2017, Google moved more than $20bn to Bermuda through a Dutch shell company, as part of a strategy called "Double Irish, Dutch Sandwich".

I put this to Pichai, who said that Google no longer uses this scheme, is one of the world's biggest taxpayers, and complies with tax laws in every country in which it operates.

I responded that his answer revealed exactly the problem: this isn't just a legal issue, it's a moral one. Poor people generally don't employ accountants in order to minimise their tax bills; large-scale tax avoidance is something that the richest people in the world do, and - I suggested to him - may weaken the collective sacrifice.

When I invited Pichai to commit there and then to Google pulling out of all tax havens immediately, he didn't take up the offer.

He did, however, make clear that he is "encouraged by the conversations around a corporate global minimum tax".

It is clear that Google is engaging with policy-makers on finding ways to make tax simpler and more effective. It is true that the company generates most of its research and revenues in the US, which is where it pays most of its tax.

Moreover, it has paid effective tax of 20% over the past decade, which is more than many companies. Nevertheless, any use of any tax haven is a reputational exposure for companies when, across the world, trillions are being borrowed, spent, and raised through taxes on ordinary folk in order to mitigate the pandemic.

The other big issues where Google is facing constant and growing scrutiny surround data, privacy, and whether or not the company has an effective monopoly in Search, where it is totally dominant.

On the last of these, Pichai makes the case that Google is a free product, and users can easily go elsewhere.

This is the same argument that Facebook has used, and Mark Zuckerberg's company received a strong endorsement from Judge James Boasberg of Washington DC last month, when he rejected a raft of anti-trust cases against the social media giant on the grounds that it didn't meet the current definition of a monopoly (that is, "the power to profitably raise prices or exclude competition").

The exchanges on privacy, data, tax and dominance in Search were perhaps the most testy of the time I had with Pichai, and can be heard in the podcast version.

Industry respect

In preparation for the interview, I spoke to more than a dozen current or former Google executives, other senior executives at big tech firms, regulators and tech-sector strategists. There was reliably strong opinion and consensus within each camp.

Those who work in the tech sector said you just cannot argue with the growth in Google's share price under Pichai. It has nearly tripled. That's a phenomenal performance. Arguing that it is explained by favourable prevailing winds in consumer behaviour - of the kind that have helped other tech giants to grow - similarly misses the point.

Google created that consumer behaviour with astonishing engineering and world-class products.

Mostly off the record, the regulators said new laws, and language, needed to be designed to exert better scrutiny on this new kind of corporate giant. Judge Boasberg's verdict on Facebook rather confirmed this. Interestingly, Lina Khan, the new 32-year-old boss of the Federal Trade Commission, has previously argued that the definition of monopoly should be expanded to reflect this new world.

The senior executives at other big tech firms were struck by what an effective public performer Pichai is. His testimonies in Congress have rarely led to drops in Google's share price. His emollient manner and grasp of detail allows him to draw poison from potentially difficult situations.

A low-profile, avuncular figure, he keeps himself largely to himself - which is partly why Google staff who watch the interview will learn a lot about him (those present said they did).

In a very revealing quick-fire round of questions, we discover he doesn't eat meat, drives a Tesla, reveres Alan Turing, wishes he'd met Stephen Hawking, and is jealous of Jeff Bezos's space mission.

It was fascinating to find all this out from such an influential figure, precisely because he doesn't make too many public pronouncements. You wouldn't, for instance, find him on Instagram riding an electric hydrofoil surfboard while holding an American flag, on US Independence Day, to the sound of John Denver's Country Roads (the version by Toots Hibbert is, of course, infinitely better).

Chief ethics officer

It was what I heard from those who worked with or for him, however, that most informed my approach.

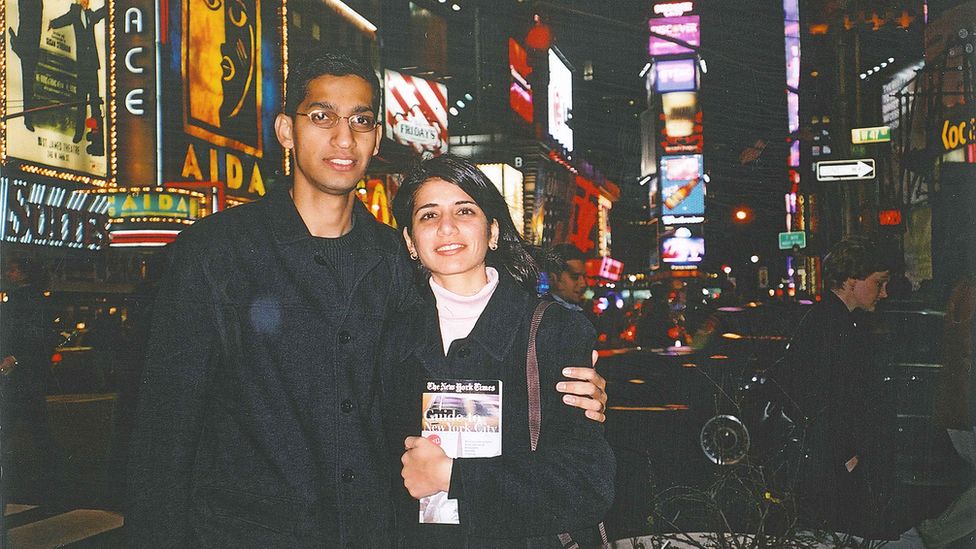

Pichai is universally regarded as an exceptionally kind, thoughtful, and caring leader. Considerate toward staff, he is, according to everyone I spoke to who knew him, genuinely committed to being an ethical example. He is an idealist when it comes to the impact of technology on improving living standards, something that has its roots in his upbringing, which we discussed at length.

He was born into a middle-class family in Tamil Nadu, in south India. Various technologies had a transformative impact on him, from the old rotary phone that they were on a waiting list for, to the scooter they all piled on to for a monthly dinner.

At Google, he won over the engineers and software developers. It helped that he was a metallurgical engineer himself, but it's still not easy; the brains trust at Silicon Valley companies includes many of the biggest egos on the planet. Yet they respect him hugely.

Pichai obeys the counter-cyclical approach to leadership appointments favoured by many head-hunters. After the necessarily pioneering, zealous, risk-taking leadership of founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, it made sense to have a lower-profile, solid, more cautious leader who would soothe public anxieties and charm public officials.

Pichai has been outstanding at these latter tasks, and the company's share price performance is remarkable. Not many people in history could say they've created a trillion dollars of value as CEO.

But the very qualities that made him a smart counter-cyclical appointment also point to potential pitfalls, according to ex-Googlers and many other close watchers. It's important to say that these people are generally tech evangelists, who have very different priorities from your average punter.

The tech evangelists are united on a few points.

First, Google is now a more cautious company than it has ever been (Google would of course dispute this, and others would say it would be a good thing if true).

Second, Google has a bunch of "Me-Too" products rather than original ideas; in the sense that it sees other people make great inventions, and then it unleashes its engineers to improve them.

Third, a lot of Pichai's big bets have failed: Google Glass, Google Plus, Google Wave, Project Loon. Google could reasonably retort that there is value in experimentation and failure. And that this rather conflicts with the first point above.

Fourth, that Google's ambition to solve humanity's biggest problems is waning. With the biggest concentration of computer science PhDs in the world in one tiny strip of land south of San Francisco, goes this argument, shouldn't Google be reversing climate change, or solving cancer? I find this criticism hard to reconcile with Pichai's record, but it is common.

Finally, that he deserves tremendous sympathy, because managing a staff as big, recalcitrant, demanding and idealistic as Google's in an era of culture wars is essentially impossible. These days Google is quite frequently in the news because of staff walkouts over diversity or pay; or because key people have left over controversial issues around identity.

With more than 100,000 staff, many of them hugely opinionated on internal message boards, and activist in nature, this is just impossible to control. There is a tension between Google genuinely embracing cognitive diversity by having people of all persuasions among its global staff, and at the same time really standing up for particular issues as a company.

Acceleration

All the above are concerns of people within the tech world who want Google to go faster. A lot of voters in polarised democracies would like big tech to slow down.

The most obvious lesson I draw from my time in Silicon Valley is that there is no chance of that happening. Acceleration is the norm: the speeding up of history is itself speeding up.

And, when I asked about whether the Chinese model of the internet - much more authoritarian, big on surveillance - is in the ascendant, Pichai said the free and open internet "is being attacked". Importantly, he didn't refer to China directly but he went on to say: "None of our major products and services are available in China."

With legislators and regulators proving slow, ineffective, and easy to lobby - and a pandemic taking up plenty of bandwidth - right now the democratic West is largely leaving it to people like Sundar Pichai to decide where we should all be heading.

He doesn't think he should have all that responsibility. Do you?